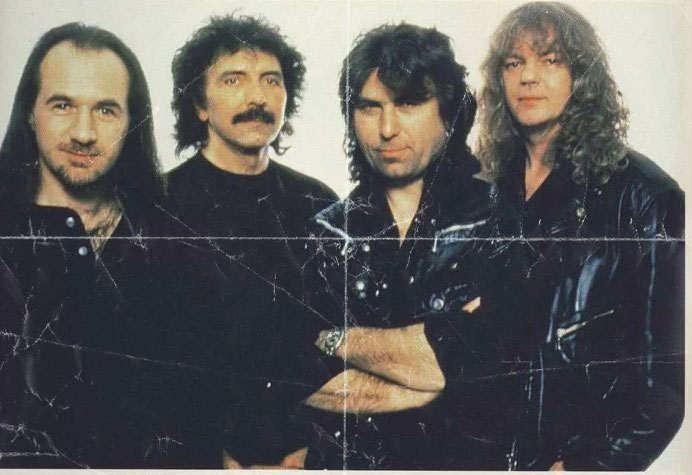

In a recent interview with Rolling Stone, bassist Neil Murray talked about his tenure in Black Sabbath.

When he was asked how he joined the band in the first place he said: “Well, it was down to Cozy [Powell, drums] again. After Whitesnake, I played a bit with Cozy and [guitarist] Mel Galley and also in a Japanese band called Vow Wow. Cozy had joined up with Tony Iommi and they’d done the [1989] album ‘Headless Cross’ for a new label. They hoped that Geezer Butler was going to go back into the band after they’d recorded that album, but he decided not to. And so they tried a few people out and then Cozy suggested me. I went along and played and it seemed to work out timing-wise. I was suitable in various ways for the band. But it’s a pretty difficult thing to replace somebody like Geezer Butler, who is the Sabbath bass player in many people’s eyes…

“But also, to have to do some extremely complicated and, in a way, fusion-y bass playing because of what Laurence Cottle had played on the ‘Headless Cross’ album before I joined. “You would have to jump from doing something very intricate to something very distorted and heavy and loud as possible. There were certain songs where you could stretch out a bit, but a lot of it was trying to be as close to Geezer as you could. It was semi-satisfying.

There’s a part of me that really enjoys playing really heavy rock onstage, which I wouldn’t necessarily sit down and listen to or play along with at home. But this is going back to the late ’80s. And if I get asked to do something like that nowadays, something very metal, I’ll often turn it down. I’m just not in that way of playing anymore.

About recording of “Tyr” he commented: “It was an attempt to get away from all the devils and black magic kind of lyrical influences on ‘Headless Cross’ to go towards the Norse mythology. But calling the album that really confused a lot of people. They didn’t even know how to pronounce it. By that point, it was very much Cozy and Tony’s band. I didn’t feel like an equal part, though perhaps it was a little different onstage.

“In the studio, it was kind of like, for me, ‘Come on, Neil. Play the bass parts.’ ‘Well, I haven’t got any vocals to play to.’ ‘That doesn’t matter. Just play what the bass part should be. That’s not really how I like to do things. I play off of everything that’s going on on the record. It wasn’t as satisfying as I would have liked, but it was an enjoyable band to be part of. You could tell that the lack of success, in America particularly, was really frustrating for Tony Iommi. I think the fact that we couldn’t even go back there to promote ‘Tyr’ persuaded him to go, ‘OK, let’s get Ronnie back in, and Geezer.’ It certainly worked, for a short time anyway.”

Finally, he also talked about the Tony Martin-era Sabbath albums that are usually slugged-off by Sabbath fans: They often don’t listen to non-Ozzy records, so they don’t really know. But it’s so easy in that kind of adolescent way, even if you’re 60 years old, to say, ‘This is amazing. This is shit.’ It’s black and white.

“To go back to Tony Martin, as powerful as he could be, he still had something of a very musical, AOR-sounding voice. And so no matter what happens, if it’s the heaviest Sabbath track in the world, it’s never going to sound like Sabbath. It’s almost going to sound too good – if you can follow my drift. That’s not what people want. They want the personality of somebody who maybe isn’t technically as good.

“I think Tony did a great job in terms of the amount of work he put into the songs and lyrics and stuff and the ideas, collaborating with Tony Iommi, but in the end, a singer is limited by the qualities of their voice. I’m not happy with how my bass is on a lot of what Sabbath did, whether it was live or in the studio, simply because I hadn’t really become Geezer in a way, or I was mixed… For example, if you listen to Tyr and then you listen to ‘Vol. 4,’ compare the volume of the bass. On ‘Vol. 4,’ it’s hitting you right between the eyes. It’s a much more sedate, ’80s mix on ‘Tyr’ where the drums are much more important.

“All through the ’80s, to be honest, it was frustrating since the whole balance of how records should sound, and how songs were written, had veered away from having a bit of freedom and a bit of importance towards the bass. It became about chugging on the guitar and incredibly loud drums. The kick and snares were right in your face, or it sounded like it was recorded in an enormously echo-y room. Something has to give, and the bass was relegated to the back of the room, as it were. That was my frustration back then.”